Shivamma (D) vs Karnataka Housing Board 2025 INSC 1104 - S.5 Limitation Act

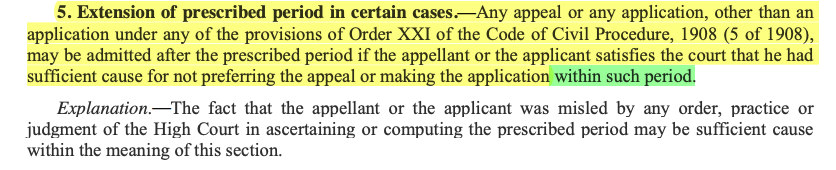

Limitation Act 1963 - Section 5 --For the purpose of condonation of delay in terms of Section 5 of the Limitation Act, the delay has to be explained by establishing the existence of “sufficient cause” for the entirety of the period from when the limitation began till the actual date of filing- If the period of limitation is 90-days, and the appeal is filed belatedly on the 100th day, then explanation has to be given for the entire 100-days. (Para 115) For the purpose of seeking condonation of delay in filing of an appeal or application, as the case may be, beyond the stipulated period of limitation, the delay in the filing has to be explained by demonstrating the existence of a “sufficient cause” that resulted in such delay for both the prescribed period of limitation as-well as the period after the expiry of limitation, up to actual date of filing of such appeal or application, as the case may be- Explanation has to be given for the entire duration from the date when the clock of limitation began to tick, up until the date of actual filing, for seeking condonation of delay. (Para 40)

Limitation Act 1963 - Section 5 - Length of the delay may be instructive but not determinative -When it comes to condonation of delay, the length of delay is immaterial, and what matters is the acceptability of the explanation. A short delay may still warrant dismissal if unsupported by sufficient cause, whereas even a long delay may be condoned if justified by circumstances demonstrating bona fides- The length of the delay functions as a contextual indicator but not a determinative factor -Section 5 of the Limitation Act does not say that such discretion can be exercised only if the delay is within a certain limit. Length of delay is no matter, acceptability of the explanation is the criterion. The criterion for condoning the delay is sufficiency of reason and not the length of the delay. A long delay naturally casts a heavier burden on the applicant to furnish cogent, credible, and convincing explanations. The proof required becomes stricter in proportion to the delay. The longer the time elapsed, the stronger the justification that must be put forth - in exercising discretion under Section 5 of the Limitation Act the courts should adopt a pragmatic approach. Whereas in the former case the consideration of prejudice to the other side will be a relevant factor so the case calls for a more cautious approach but in the latter case, no such consideration may arise and such a case deserves a liberal approach. No hard-and-fast rule can be laid down in this regard. The court has to exercise the discretion on the facts of each case keeping in mind that in construing the expression “sufficient cause”, the principle of advancing substantial justice is of prime importance. (Para 128-134)

Limitation Act 1963 - Section 5 - Strong case on merits is no ground for condonation of delay. When an application for condonation of delay is placed before the court, the inquiry is confined to whether “sufficient cause” has been demonstrated for not filing the appeal or proceeding within the prescribed period of limitation- The purpose of Section 5 of the Limitation Act is not to determine whether the claim is legally or factually strong, but only whether the applicant had a reasonable justification for the delay. (Para 140-143)

Limitation Act 1963- Section 5 - The appellate court cannot embark upon an inquiry to enter a finding based on its likes or dislikes. The true test is to see, if it had been up to the appellate court, could the delay have been plausibly condoned for the same reason that was assigned by the court below, by looking into the material on record to see if the ingredients of Section 5 of the Limitation Act were fulfilled or not. If the ingredients of the provision is found to not have been fulfilled, the appellate court can and ought to interfere with the order of the court below. However, if the aforesaid is answered in an affirmative, all that remains to be seen is that the discretion that was exercised in condoning the delay was not done mechanically, arbitrarily or capriciously, and was exercised for the purpose of advancing the cause of justice. Only where the exercise of discretion was clearly wrong, would the court sitting in appeal, interfere with the same. (Para 169-170)

Limitation Act 1963 - Section 5-Condonation of delay is to remain an exception, not the rule. Governmental litigants, no less than private parties, must demonstrate bona fide, sufficient, and cogent cause for delay. Absent such justification, delay cannot be condoned merely on the ground of the identity of the applicant - Twofold test: First, that State or any of its instrumentalities cannot be accorded preferential treatment in matters concerning condonation of delay under Section 5 of the Limitation Act. The State must be judged by the same standards as any private litigant. To do otherwise would not only compromise the sanctity of limitation. The earlier view, insofar as it favoured a liberal approach towards the State or any of its instrumentality is no more the correct position of law. Secondly, that the habitual reliance of Government departments on bureaucratic red tape, procedural bottlenecks, or administrative inefficiencies as grounds for seeking condonation of delay cannot always, invariably accepted as a “sufficient cause” for the purpose of Section 5 of the Limitation Act. If such reasons were to be accepted as a matter of course, the very discipline sought to be introduced by the law of limitation would be diluted, resulting in endless uncertainty in litigation. (Para 213)

Precedent -Where, however, the law, during the pendency of the appeal, has undergone a shift, there the court sitting in appeal, would not only be bound by the change in position of law, but would be well empowered to interfere with the lower courts decision, on that ground alone, notwithstanding the fact, that when the original decision was rendered, that was not the position of law- A decision of the court which either overrules or results in a change in position of law, generally operates retrospectively (Para 225)

Interpretation of Statutes-While construing a provision, a meaningful effect should be given to each and every word used by the legislature within the text of the provision. In interpreting a provision, a coherent meaning has to be culled out from the entire scheme of the Act and the provisions contained therein. The entire text of the provision must be read holistically with the entire Act, in toto, and harmoniously integrated with the other provisions to preserve internal consistency. Stray lines or words of a provision cannot be isolated or construed in fragments, detached from the remaining words and expressions of the provision as-well as the other provisions within the statute. (Para 38) The legislature always speaks through the statute it enacts, and its intention behind any provision or provisions thereof, is to be gathered from the language used in the provision along with the avowed objects with which the same came to be enacted. In construing or interpreting a provision, any deviation from the legislative intent that backs the particular statute containing the said provision cannot be done casually. Mere omission of few stray words, does not detract or take away the lofty intent behind enacting the statute and cannot always be interpreted to impute a contrary intent unless the same is apparent and supported by some other salutary object with which such omission may have been made. (Para 74)

Q&A Made Using NotebookLM

1. What is Section 5 of the Limitation Act and what is the meaning of "sufficient cause" for condoning delays?

Section 5 of the Limitation Act, 1963, grants courts discretionary power to admit an appeal or application (excluding those under Order XXI of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908) even after the prescribed limitation period has expired, provided the appellant or applicant demonstrates "sufficient cause" for the delay. This "sufficient cause" is an elastic term, not precisely defined in the Act, allowing for judicial interpretation based on the specific facts and circumstances of each case.

To establish "sufficient cause," the party must prove that their failure to file within the prescribed time was not due to negligence, lack of diligence or vigilance, indolence, inactivity, or a lack of bona fides. The explanation offered should be genuine, plausible, and consistent with ordinary human conduct. While a liberal, pragmatic, and justice-oriented approach is generally favored, courts must avoid condoning delays due to gross negligence, deliberate inaction, casual indifference, or concocted explanations. The primary aim is to advance substantial justice without undermining the law of limitation.

2. For what period does "sufficient cause" need to be explained when seeking condonation of delay under Section 5?

There has been a divergence of opinion on the precise period for which "sufficient cause" must be demonstrated. The Supreme Court in the present case clarifies that "sufficient cause" must be explained for the entire duration from the date the limitation period began to run until the actual date of filing the appeal or application. This means the explanation must cover both the original prescribed period of limitation and any period of delay that occurred after the limitation expired until the actual filing date.

This interpretation rejects earlier views that only required an explanation for the period from the last day of limitation until the actual filing date. The court emphasizes that considerations of diligence, bona fides, and inaction during the entire prescribed period are relevant, as Section 5's language, when read holistically with terms like "after the prescribed period" and "for not preferring the appeal or making the application," supports this broader scope.

3. How does the length of the delay influence the court's decision on condonation?

The length of the delay is instructive but not determinative of whether a delay should be condoned. What truly matters is the acceptability and sufficiency of the explanation provided. A short delay may be denied if there is no "sufficient cause," while a long delay can be condoned if adequately justified by circumstances demonstrating bona fides and diligence.

However, a longer delay naturally places a heavier burden on the applicant to furnish cogent, credible, and convincing explanations. The required proof becomes stricter in proportion to the delay, meaning the justification must be stronger as the elapsed time increases. The court's focus remains qualitative, on the adequacy of the cause, rather than quantitative, on the mere duration of the delay.

4. Should courts consider the merits of the underlying case when deciding on a delay condonation application?

No, the merits of the underlying case should generally not be considered when deciding an application for condonation of delay. The inquiry at this stage is strictly confined to whether "sufficient cause" has been demonstrated for the delay in filing the appeal or proceeding within the prescribed period of limitation.

Considering the merits prematurely would blur the lines between preliminary procedural questions and substantive adjudication, leading to an inequitable and inconsistent application of the law. The purpose of Section 5 is not to assess the strength of a claim but to determine if there was a reasonable justification for the delay. Courts must maintain judicial discipline to ensure a neutral and unprejudiced setting for the ultimate adjudication of rights.

5. What is the standard for an appellate court interfering with a lower court's decision to condone or refuse to condone delay?

An appellate court has a different standard when reviewing a lower court's discretionary order on delay condonation. If the lower court refused to condone the delay, the appellate court has more leeway and can consider the cause shown for the delay afresh, forming its own finding without being strictly bound by the lower court's conclusion.

However, if the lower court granted condonation of delay, the appellate court should "ordinarily not interfere" unless the discretion was exercised "unreasonably or capriciously," ignored relevant facts, acted with material irregularity, or was "clearly wrong." The appellate court's role is to ensure a "proper exercise of discretion," which involves a two-pronged inquiry: first, into the existence of "sufficient cause" based on the material on record (checking for legal conformity, material irregularity, or lack of evidence), and second, into the exercise of discretion itself (ensuring it was not mechanical, arbitrary, or capricious, and advanced justice without grave prejudice). The appellate court must determine if the lower court's view was plausible and not contrary to law, but it should not substitute its own plausible view merely because another is available.

6. Has the approach to condoning delays for government entities changed over time?

Yes, there has been a significant shift in jurisprudence regarding the condonation of delay for the State and its instrumentalities. Previously, courts afforded a degree of latitude, acknowledging bureaucratic complexities and the "impersonal machinery" of government, often justifying delays as unavoidable. This approach was partly driven by the concern that dismissing governmental cases on technicalities could harm public interest.

However, the landmark decision in Postmaster General v. Living Media India Ltd. (2012) marked a pivotal change. This ruling emphasized that the law of limitation binds the government no less than private litigants. It rejected the "impersonal machinery" and "bureaucratic methodology" excuses in light of modern technology, insisting on reasonable and acceptable explanations, and bona fide efforts. Subsequent judgments (like Bherulal and University of Delhi) have reiterated that governmental lethargy, tardiness, or indolence are generally not "sufficient cause" for delay. The focus has shifted to promoting accountability and diligence in public litigation, recognizing that public interest is best served by efficient governmental functioning rather than by condoning its lapses.

7. What is the current stance on "bureaucratic lethargy" or "red-tapism" as a "sufficient cause" for delay by the State?

The current stance, following the Postmaster General decision and subsequent rulings, is that "bureaucratic lethargy" or "red-tapism" are generally no longer accepted as "sufficient cause" for condonation of delay by the State or its instrumentalities. While the court recognizes that some bureaucratic procedures are inherent, it now demands genuine and bona fide explanations that demonstrate reasonable diligence despite these complexities.

The distinction is made between a mere "excuse" (denying responsibility without truth) and a genuine "explanation" (demonstrating efforts and reasons free from gross negligence or indifference). Courts are now circumspect and reluctant to accept such explanations, requiring exceptional instances where the government entity can prove it acted with vigilance and promptitude, and the delay occurred despite sincere efforts. The earlier practice of granting "leeway" to the State has largely been abandoned to uphold the discipline of limitation and foster accountability.

8. Why is public interest now considered to be better served by enforcing timely action rather than by routinely condoning governmental delays?

Public interest is now considered better served by enforcing timely governmental action and upholding the law of limitation for several reasons:

- Undermining Public Policy: Limitation laws are founded on the public policy maxim interest reipublicae ut sit finis litium ("it is in the interest of the State that there be an end to litigation"). Routinely condoning delays, even for the State, undermines this fundamental principle of bringing finality to disputes.

- Institutionalizing Inefficiency: Permitting condonation as a matter of course for the government would institutionalize inefficiency, incentivize indolence, and erode accountability within the administration. If officials are assured their lapses will be excused under the guise of "public interest," there is little motivation for diligence.

- Betrayal of Public Trust: The State acts as a trustee of the people's interest. Consistently failing to protect that interest by allowing limitation periods to lapse, while claiming "public interest" to excuse such failures, is seen as a betrayal of this trust.

- Equality Before Law: Granting preferential treatment to the State in matters of limitation would compromise the principle of equality before the law, creating an artificial distinction between government entities and private litigants.

- Promoting Responsible Governance: Public interest lies in compelling efficiency, responsibility, and timely decision-making from government departments, rather than condoning their negligence. This fosters a culture of accountability.

- Prejudice to Private Litigants: Unwarranted condonation of significant delays (e.g., 11 years in the Shivamma case) forces private litigants into perpetual battles against the "enormous State," frustrating the fruits of their decrees and causing undue hardship.

Therefore, the courts now emphasize that public interest is synonymous with the enforcement of the rule of law, certainty in legal rights, and a diligent administrative machinery, rather than merely protecting governmental indifference.

Very important #SupremeCourt judgment on Limitation Act.#SupremeCourt has held that for the purpose of condonation of delay in terms of Section 5 Limitation Act, the delay has to be explained by establishing the existence of “sufficient cause” for the entirety of the period… https://t.co/SC9n3JqFIm pic.twitter.com/rdKlAdMNGf

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) September 12, 2025

#SupremeCourt holds that the criterion for condoning the delay under Section 5 Limitation Act is sufficiency of reason and not the length of the delay.

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) September 12, 2025

Even a long delay may be condoned if justified by circumstances demonstrating bona fide, the Court said. https://t.co/SC9n3JqFIm pic.twitter.com/I2U0LbEUfF

So #SupremeCourt 2 Judges Bench noted that there is a 1962 judgment which interpreted Section 5 Limitation Act in a particular way. But then, it proceeds to adopt contrary interpretation. https://t.co/SC9n3Jq7SO pic.twitter.com/3ADVSrKo5k

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) September 12, 2025