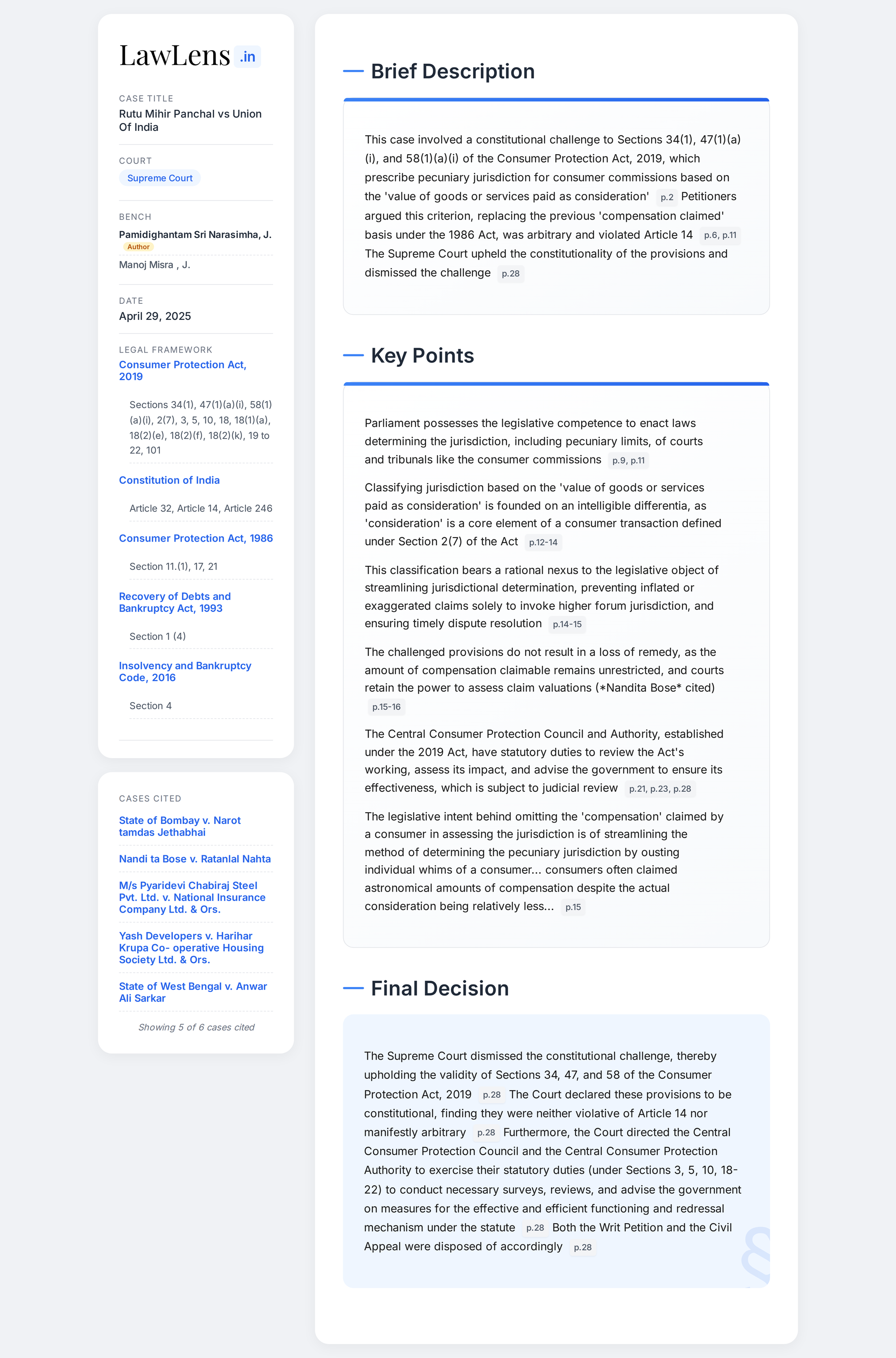

Rutu Mihir Panchal vs Union Of India 2025 INSC 593 - Consumer Protection Act - Pecuniary Jurisdiction Prescription - Constitutional Validity Upheld

Consumer Protection Act 2019 - Sections 34(1), 47(1)(a)(i) and 58(1)(a)(i) -Constitutional Validity of provisions prescribing pecuniary jurisdictions of the district, state and national commissions on the basis of value of goods and services paid as consideration, instead of compensation claimed upheld - The said provisions are constitutional and are neither violative of Article 14 nor manifestly arbitrary- (Para 13) There is no right or a privilege of a consumer to raise an unlimited claim of compensation and thereby chose a forum of his choice for instituting a complaint - classification of claims based on value of goods and services paid as consideration has a direct nexus to the object of creating a hierarchical structure of judicial remedies through tribunals.(Para 11.1)

Consumer Protection Act 2019 - Sections 3, 5, 10, 18 to 22 - Central Consumer Protection Council and the Central Consumer Protection Authority shall in exercise of their statutory duties under sections 3, 5, 10, 18 to 22 take such measures as may be necessary for survey, review and advise the government about such measures as may be necessary for effective and efficient redressal and working of the statute.

Constitution of India - Article 246 -Parliament has the legislative competence to enact the Consumer Protection Act- Entry 95 of List I read with Entries 11-A and 46 of List II- The legislative competence to prescribe jurisdiction and powers of a court, coupled with the power to constitute and organize courts for administration of justice, takes within its sweep the power to prescribe pecuniary limits of jurisdiction of the courts or tribunals. Parliament has the legislative competence to prescribe jurisdiction and powers of courts. This power extends to prescribing different monetary values as the basis for exercising jurisdiction. (Para 9)

Constitution of India - Article 32- Performance Audit of the Statute - A peculiar feature of how our legislative system works is that an overwhelming majority of legislations are introduced and carried through by the Government, with very few private member bills being introduced and debated. In such circumstances, the judicial role does encompass, in this Court’s understanding, the power, nay the duty to direct the executive branch to review the working of statutes and audit the statutory impact. It is not possible to exhaustively enlist the circumstances and standards that will trigger such a judicial direction. One can only state that this direction must be predicated on a finding that the statute has, through demonstrable judicial data or other cogent material, failed to ameliorate the conditions of the beneficiaries. The courts will also do well, to at the very least, arrive at a prima facie finding that much statutory schemes and procedures are gridlocked in bureaucratic or judicial quagmires that impede or delay statutory objectives. This facilitative role of the judiciary compels audit of the legislation, promotes debate and discussion but does not and cannot compel legislative reforms. (Para 12.5)

Supreme Court upholds constitutional validity of the provisions of the Consumer Protection Act 2019 which prescribes pecuniary jurisdictions Consumer commissions on the basis of value of goods and services paid as consideration, instead of compensation claimed. https://t.co/SzSJ289nBO pic.twitter.com/6n17htFXmR

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) April 29, 2025

Interesting 😇 https://t.co/SzSJ289Vrm https://t.co/iKg3DDz3BQ

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) April 29, 2025