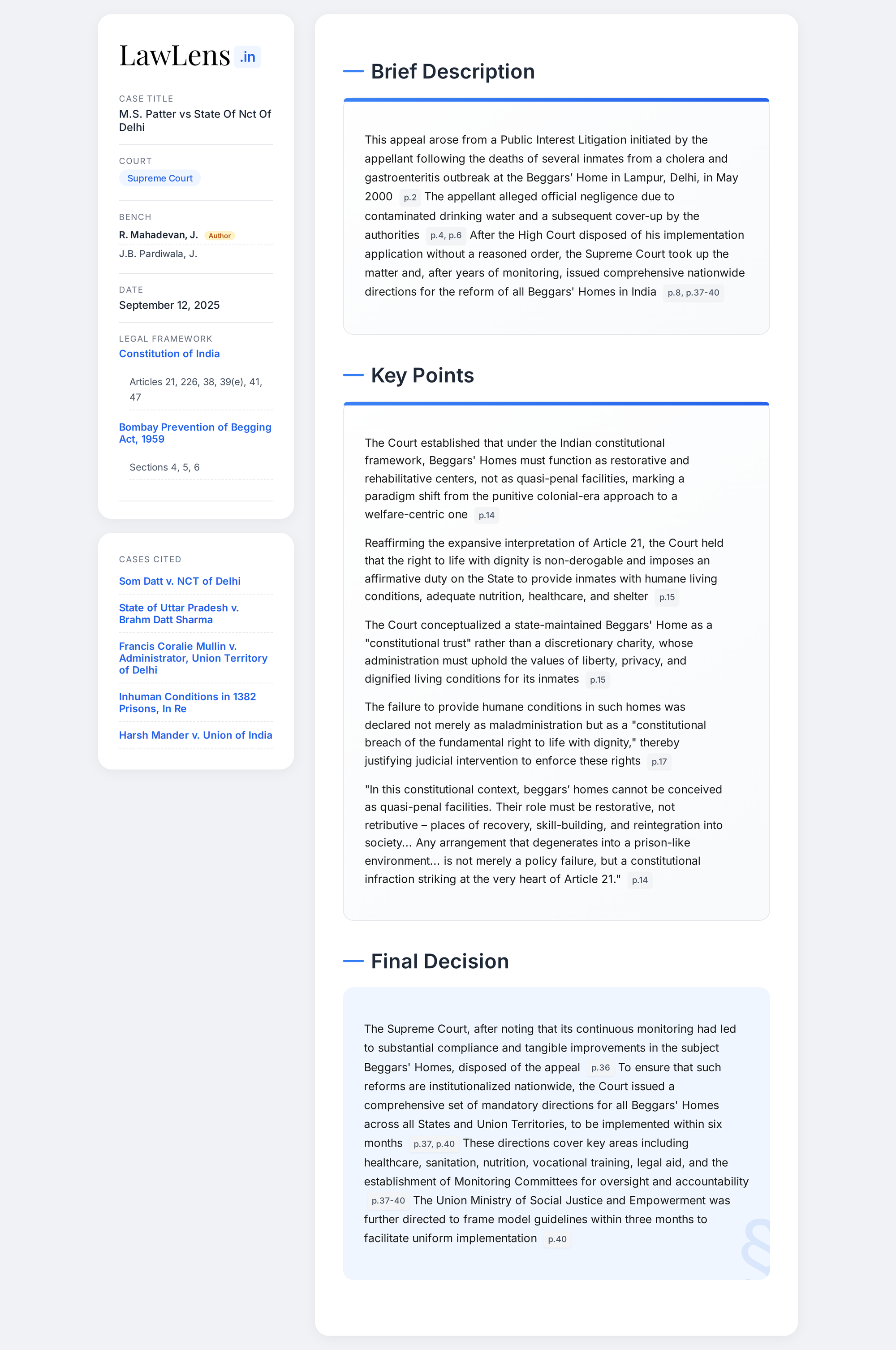

M.S. Patter v. State of NCT of Delhi 2025 INSC 1115 - Beggars' Homes

Constitution of India - Article 21 - Beggars' Home -State’s responsibility towards indigent persons is affirmative and non-derogable. A beggars’ home, maintained by the State, is thus a constitutional trust, not a discretionary charity.- The failure to ensure humane conditions in such homes does not merely amount to maladministration; it represents a constitutional breach of the fundamental right to life with dignity, thereby inviting judicial intervention - Directions issued in respect of all Beggars’ Homes across the country. (Para 16-23)

Constitution of India - Article 21 -Article 21 of the Constitution of India, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, has been interpreted by this Court in an expansive and purposive manner. It is no longer confined to mere animal existence; it embraces within its fold the rights to dignity, health, shelter, privacy, and humane treatment, with heightened protection for the most vulnerable groups- State’s responsibility towards indigent persons is affirmative and non-derogable. (Para 16)

Hello !!

We are a small group of lawyers and law students who regularly read Supreme Court judgments and make notes of it. This project is supported by a group of 1000+ subscribers ! We urge you to subscribe to us and access our Supreme Court Daily & Monthly Digests and subject wise digests.

Q&A generated using Google NotebookLM

1. What was the initial incident that led to the M.S. Patter v. State of NCT of Delhi case?

The case originated from a Public Interest Litigation filed by M.S. Patter after news reports in May 2000 exposed a dire situation at the Beggars' Home at Lampur (Narela), Delhi. Multiple news articles reported dozens of beggars suffering from cholera and gastroenteritis, with many admitted to the hospital, and at least six deaths occurring among the inmates. These reports highlighted severe negligence, with various Delhi government departments accusing each other of responsibility. The appellant alleged that authorities were misleading the public and concealing the true facts about the deaths and the conditions in the home.

2. What were the primary causes identified for the health crisis at the Beggars' Home?

Investigations, including a magisterial inquiry and reports from committees, revealed that the deaths and widespread illness were primarily attributable to severe contamination of the drinking and cooking water supply. The water was found to contain E. coli, indicating faecal contamination, and vibrio cholera bacteria. This was linked to a non-functioning chlorinator plant, unsatisfactory hand pumps, and the leakage of water from a bathroom wall contaminating the water sources. Additionally, the committee noted shocking lapses such as human excreta mixing with water, food unfit for human consumption, and generally unhygienic conditions.

3. How has the Indian legal framework evolved in its approach to "beggars' homes" since the colonial era?

Historically, during British rule, vagrancy laws in India, like the Bombay Prevention of Begging Act, 1959 (BPBA), were punitive tools for social control, mirroring Victorian and Edwardian views of poverty as a moral failing. These laws allowed for arrest, detention, and forced confinement based on appearance rather than a substantive offense.

However, the post-1950 Indian Constitutional framework signifies a decisive normative shift towards a welfare-centric State committed to dismantling structural inequalities and ensuring individual dignity. This ethos is embodied in the Directive Principles of State Policy (Articles 38, 39(e), 41, 47) and especially Article 21, which guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, interpreted broadly to include dignity, health, and humane treatment. Consequently, beggars' homes are now to be conceived as restorative, not retributive, places for recovery, skill-building, and reintegration, rather than quasi-penal facilities. The Supreme Court emphasizes that any environment resembling a prison, characterized by overcrowding, unhygienic conditions, or denial of basic rights, constitutes a constitutional infraction.

4. What are the constitutional obligations of the State towards individuals detained in beggars' homes, according to the Supreme Court?

The Supreme Court unequivocally states that the State's responsibility towards indigent persons is affirmative and non-derogable. Beggars' homes, maintained by the State, are considered a constitutional trust, not a discretionary charity. Their administration must uphold constitutional morality, ensuring liberty, privacy, bodily autonomy, and dignified living conditions. Citing Article 21, the right to life extends to living with human dignity, including adequate nutrition, clothing, shelter, and humane treatment. Since these protections are afforded even to convicts, they apply a fortiori to residents of beggars' homes, many of whom are victims of systemic issues like poverty or mental illness, not offenders. Their confinement, if necessary, must be protective and include comprehensive rehabilitation services. The failure to provide humane conditions in these homes is a constitutional breach of the fundamental right to life with dignity.

5. What specific improvements and remedial measures were directed by the Supreme Court for beggars' homes across the country?

The Supreme Court issued comprehensive directions for all beggars' homes nationwide, encompassing:

- Preventive Healthcare and Sanitation: Mandatory medical screening upon admission, monthly health check-ups, disease surveillance systems, and strictly enforced minimum hygiene standards including potable water, functional toilets, and pest control.

- Infrastructure and Capacity: Independent third-party infrastructure audits biennially, strict adherence to sanctioned capacity to prevent overcrowding, and adequate provision for safe housing, ventilation, and open spaces.

- Nutrition and Food Safety: Appointment of qualified dieticians to verify food quality and nutritional standards, and standardized dietary protocols.

- Vocational Training and Rehabilitation: Establishment or expansion of vocational training facilities, partnerships with various agencies for diverse training programs, and periodic assessments of rehabilitation effectiveness.

- Legal Aid and Awareness: Informing inmates of their legal rights and designating panel lawyers from State Legal Services Authorities for regular visits and free legal assistance.

- Child and Gender Sensitivity: Separate facilities for women and children ensuring privacy, safety, childcare, education, and counselling. Children found begging must be referred to child welfare institutions, not beggars' homes.

- Accountability and Oversight: Constitution of Monitoring Committees for annual reports and accurate record-keeping of illnesses, deaths, and remedial actions. Compensation to next of kin for deaths due to negligence and initiation of departmental/criminal proceedings against responsible officials.

- Implementation and Compliance: Maintenance of a centralized digital database of all inmates and implementation of all directions within six months.

6. How did the High Court initially address the issues, and what led the appellant to approach the Supreme Court?

The High Court initially disposed of the Public Interest Litigation in October 2001 after taking note of affidavits and an interim committee report. It directed departmental proceedings against erring officials and measures to make the homes more habitable within six months. The High Court considered the first and third prayers (fixing responsibility and punishing officials) satisfied as an inquiry had been held and responsibility fixed. For compensation, it stated that claims would be examined if relations came forward.

However, the appellant subsequently filed an application complaining of non-compliance with the 2001 order. The High Court disposed of this application without a speaking order, merely granting liberty to the appellant to approach another forum if dissatisfied. Aggrieved by this lack of a reasoned order and the perceived non-compliance, particularly the absence of a final report from the committee and the alleged continued poor conditions, the appellant appealed to the Supreme Court.

7. What role did the Amicus Curiae and various committee reports play in the Supreme Court's long-term monitoring of the Beggars' Homes?

The Amicus Curiae, Mr. Ranjit Kumar, played a crucial role by assisting the Court, analyzing reports, and suggesting guidelines and directions. Over the years, the Supreme Court appointed and relied on various committees, including the one initially appointed by the High Court, and later involved the Delhi Legal Services Authority (DSLSA) and dieticians from GTB Hospital.

These committees and individuals conducted site visits, submitted detailed reports outlining "pathetic" and "miserable" conditions, and identified persistent deficiencies in infrastructure, hygiene, food quality, staff, and security. The reports were instrumental in informing the Court's continuous monitoring, leading to a series of specific directions for improvements in areas like staff appointments, building renovation, drainage, ventilation, laundry facilities, hot water supply, food quality, and the installation of security guards and CCTV cameras. The Court consistently pressed for compliance, deprecating laxity and holding officials personally responsible for non-compliance.

8. What is the overarching principle articulated by the Supreme Court regarding the "criminalization of poverty" in the context of begging laws?

The Supreme Court firmly rejected the "criminalization of poverty" as inconsistent with the Indian Constitution's welfare-centric ethos. It noted that colonial-era vagrancy laws treated poverty as a moral failing, leading to punitive measures. However, post-independence, the constitutional framework mandates a compassionate State that acts as a trustee for the well-being of the poor and destitute.

The Court emphasized that while states have a legitimate interest in public order and the rehabilitation of vulnerable persons, the design and implementation of begging laws "must conform to constitutional guarantees, uphold individual dignity, and reflect constitutional morality, ensuring that regulation does not degenerate into the criminalisation of poverty." The Delhi High Court had already struck down provisions of the BPBA criminalizing begging as violative of fundamental rights. The Supreme Court's ruling underscores that individuals in beggars' homes are often victims of structural poverty or social exclusion, and their confinement must be for protective custody and rehabilitation, not as punishment for their condition.

Supreme Court Mandates Sweeping Reforms for Beggars' Homes Nationwide; Declares Humane Conditions a Constitutional Right https://t.co/sjMNnt1HAF pic.twitter.com/SVFOI4Lhxg

— CiteCase 🇮🇳 (@CiteCase) September 13, 2025